Course. Judgment and Decision Making

- Raise students’ awareness of perception, judgement and decision making.

- Familiarise students with various decision-making models and tools.

- Improve students’ decision-making skills.

CASE STUDY

Acknowledging Cognitive Biases in Decision Making: Mental Accounting

Click to open

The concept of mental accounting, developed by economist Richard H. Thaler, refers to the way we manage and organise our financial activities and it may well illustrate how cognitive biases impact the decision-making process. Though Thaler defined mental accounting as ‘the set of cognitive operations used by individuals and households to organize, evaluate, and keep track of financial activities’ (Richard H. Thaler, Mental Accounting Matters, Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 12: 183-206, 1999), he went on describing how mental accounting also impacted corporate financial decisions, (Ibid.) Thaler pointed out that ‘the primary reason for studying mental accounting is to enhance our understanding of the psychology of choice.’ (Ibid.) It is argued that, if left unacknowledged, mental accounting may result in irrational decisions regarding investment or spending. For example, research has indicated that we are more willing to pay for goods when we pay by credit card, not in cash. We tend to differentiate between the ways we earn money and in case of any unexpected financial gain, such as gambling winnings or any windfall, we are more likely to spend the money or make a high-risk investment. Yet, once these cognitive biases are recognised and analysed, mental accounting may be used as a tool for reinforcement of positive behaviour.

- How would you decide if you could really afford that small treat of a cookie (2 euros) every working day at a coffee shop?

- You have bought 100 shares of stock at $10 a share. Would you sell that stock when the price of stock fell, that is, would you sell the loser?

See answers

- It is best to add up costs over a month or even a year. That’s how we can make a rational decision whether or not we can afford a product/service and avoid overspending on items we do not really need or want but we still tend to buy, just because, for example, they are heavily discounted. Lots of ads may exploit irrational spending, for example ads selling cars that cost ‘only 2 euros a day.’

- Thaler explains that ‘a rational investor will choose to sell the loser because capital gains are taxable and capital losses are deductible.’ He argues that ‘because closing an account at a loss is painful, a prediction of mental accounting is that people will be reluctant to sell securities that have declined in value.’ He further explains: ‘… suppose an investor needs to raise some cash and must choose between two stocks to sell, one of which has increased in value and one of which has decreased. Mental accounting favors selling the winner (Shefrin and Statman, 1987) whereas a rational analysis favors selling the loser.’

See more

Making Decisions the Right Way – Which Decision Type Should I Choose?

Click to open

You are a team leader at ICT Consult Ltd., a small company that works on IT projects for different organizations. There are five great IT specialists in your team. You know your strengths and weaknesses very well and you always manage to distribute your workload so that you can complete the projects on time and with excellent quality. One day Eric, the most experienced IT specialist on the team, comes to you and files his resignation letter. You are utterly surprised – why would this valuable team member want to leave the company and could you do something about it?

Your task includes the following steps:

- Define the problem and explain the potential causes.

- Select one of the causes as most probable and prepare at least two satisfactory solutions to this problem.

- Identify the main criteria for making your decision (selecting a solution), compare the two solutions against your criteria and justify your decision.

- Identify the type of the decision that you have made.

See answers

Since the task might have multiple outcomes, here is one possible solution:

1. Define the problem and explain the potential causes.

The problem is that a key employee leaves our team which will cause friction, additional workload, loss of team efficiency and cohesion, or even motivation.

Potential causes for leaving the company may be a lack of opportunities for development (this is the most experienced team member and he would expect more), a job offer from a competitor, personal issues, willingness to change the work routine.

2. Select one of the causes as most probable and prepare at least two satisfactory solutions to this problem.

The most probable cause is the lack of development opportunities. Two possible solutions for this problem are: 1) form a new team within the company and put Eric in the leadership position; 2) empower Eric to make his own decisions for certain aspects of the work, provide more freedom and challenging tasks.

3. Identify the main criteria for making your decision (selecting a solution), compare the two solutions against your criteria and justify your decision.

The main criteria would be time needed to implement the decision; likelihood to retain Eric; cost for the company; effect on team performance.

Here is the comparison of the two solutions:

|

Criterion |

Solution 1 |

Solution 2 |

|

Time |

Long timeframe |

Very little |

|

Retention |

More likely |

Less likely |

|

Cost |

Costs related to organizational changes |

No specific cost |

|

Team performance |

Detrimental to the original team. Unknown for the new team |

Improvement for the original team |

Based on the criteria analysis, we suggest making the decision to apply the second solution even though the first would have higher chances of success. The risks associated with forming a new team are very high and we cannot measure the outcomes.

4. Identify the type of the decision that you have made.

This decision has been made in uncertain circumstances, it is a nonprogrammed, tactical, and specific decision.

See more

Developing Student Soft Skills with Emphasis on Intercultural Communication and Leadership Skills

Click to open

Need identified: bridging the gap in soft skills development in higher education (HE)

Assignment: You work at the International Office of your university and you are responsible for further internationalisation and digitalisation of the university programs with view of improving the students’ employability prospects in a continuously globalised job market and in particular developing intercultural communication skills and leadership. You have several ideas along these lines. One of your priorities is to work with other Erasmus+ universities (using EU project funding) in order to multiply the effect and provide structured opportunities for work in international teams (students/lecturers/administration staff). You have to take into account collaboration with the business with view of better employability options for students.

Put down your ideas in bullet points.

Share your ideas with your colleagues in a brainstorming session. Then take a group decision, using a chosen decision-making method, e.g. DECIDE:

|

D |

Define the problem |

|

E |

Establish the criteria |

|

C |

Consider all the alternatives |

|

I |

Identify the best alternative |

|

D |

Develop and implement a plan of action |

|

E |

Evaluate and monitor the solution |

Finally compare your proposal with the practise-based example in the suggested answers.

See answers

Defining the problem: Bridging the gap in soft skills development by putting an emphasis on intercultural communication and leadership skills development, achieving results such as higher motivation and higher employability of graduates in a continuously globalised labour market.

Establishing the criteria: internationalisation, digitalisation, structured cost-effective opportunities for international collaboration, scientific approach to skills shortage identification (focus on intercultural communication and leadership), sustainability.

Depending on the group member input, you will have probably identified several alternatives, choosing the best option and plan of action as well as establishing mechanisms for evaluating the results.

Compare your results with the following real life practice example:

Brief description

PROMINENCE (Promoting Mindful Encounters through Intercultural Competence and Experience, 2017-2020) is an international project co-funded by the Erasmus+ Programme Strategic Partnerships in Higher Education. The strategic partnership project strengthens links between partner universities, students and SMEs as potential employers. It offers deliverables that help develop intercultural competence, business skills and leadership skills of SMEs employees, business students and faculty members.

The PROMINENCE teams from seven EU universities: Aschaffenburg (Germany), University of Economics in Bratislava (Slovakia), Debrecen (Hungary), Katowice (Poland), Mont Blanc Savoie (France), Seinäjoki (Finland) and the University of Economics - Varna (Bulgaria), completed the project, which is an excellent example of higher business education internationalization.

It is a research-led initiative (i.e. it meets the scientific approach criterion) targeting to improve student engagement through experiential learning while enhancing their employability prospects. The research involved 3 large-scale surveys (with the business, students and lecturers from the 7 EU countries. (See the reference section).

Developing student soft skills in a meaningful way is ensured by using: 1/ PROMINENCE Interactive OEPR (open educational resources platform), which ensures cost-effectiveness and 2/ student international workshops (3+ Intensive Programmes), which provide structured opportunities for work in international teams.

Key activities and forms of support of soft skills and employability in HE:

Career days at the partner universities; specialised IPs (Intensive Programs) – involving representatives from all 7 partner universities (students and academic staff) within the project framework (See the reference section for IPs); new courses introduced at universities, e.g. ‘Intercultural Communication and Leadership’, using PROMINENCE Interactive as a primary source (cost-effectiveness and multiplying effect in the 7 universities); soft skills courses offered to SMEs.

Sustainability has been further ensured since the project was over by using other opportunities, e.g. Dukenet annual international events or using the format of the most successful online PROMINENCE Intensive Program ‘Practicing Cultural Intelligence across Cultures’. Dukenet is a consortium of 17 EU universities, providing several international student events annually: structured opportunities for students for developing various skills: real/disperse teamwork, problem solving, cultural and emotional intelligence applied in business context, creativity, decision making, negotiations, presentation skills.

Outputs and outcomes: Highly positive feedback. Close interaction between HE and SMEs.

Key success factors in implementing this initiative: Ensuring sustainability is key for providing regular Intensive Programs, developing students’ employability skills. Inviting presenters from businesses. Practical skills development.

See more

BEST PRACTICES

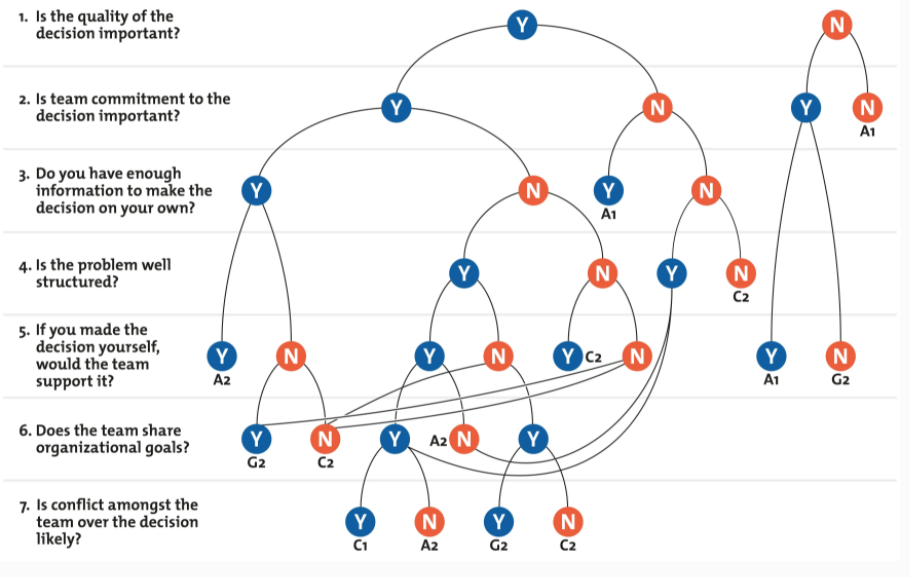

Vroom-Yetton-Jago Normative Decision Model

Click to open

The Vroom-Yetton-Jago normative decision model is a decision-making tree which helps business leaders determine whether they need to involve others in the decision-making process and to what extent. Leaders elicit information by asking a series of questions about the situation, possible decisions and consequences to decide on the degree of involvement of others. As a result, the style of decision making may vary from autocratic (when the leader makes a decision on their own) to consultative to group based. This model may be illustrated by this diagram designed by MindTools, with A1 and A2 referring to an autocratic style of decision making, C1 and C2 to a consultative one, and G2 to a group-based style of decision making:

See more

Decision-Making Tool for Pilots

Click to open

FAA’s basic assumption is that not only can good judgement be learned from experience - it can be taught. The Aeronautical Decision Making tool, ADM, builds upon conventional decision making to help decrease the likelihood of errors in the cockpit. It is a structured, systematic approach using risk-management tools called PAVE and 3P, and a decision-making model DECIDE, modified for pilot’s situations.

PAVE defines the four major hazards of flight: Pilot, Aircraft, enVironmental and External. Hazards create risk, making PAVE critical in risk management and ultimately preflight and in-flight aeronautical decision making. The Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (PHAK) defines risk ‘as the future effect of a hazard which is not controlled or eliminated.’

Two models for practical risk management are used. The first invokes the Perceive-Process-Perform or 3P model. First, Perceive a given set of circumstances for your flight using PAVE. Then Process the circumstances by evaluating their effect on flight safety with CARE (Consequences, Alternatives, Reality, External pressures). Lastly, Perform the best course of action using TEAM (Transfer, Eliminate, Accept, Mitigate). This process should become largely automated. The degree of a risk can be weighed in terms of exposure, severity and probability. An exposure could include the number of people or resources that would be affected. Severity is the extent of possible loss. Last, what is the probability that a hazard will cause a loss?

DECIDE is a simple six-step tool offering you a logical way to make decisions. In the current context it is also considered a risk management tool. Your senses Detect that an unexpected event occurred. You use your insight and experience; you objectively analyse all available information. Then you Estimate the nature of the issue and how severe it might be. A caution: If you incorrectly define the problem, incorrect decision making will follow. Choose a course of action that leads to a desired outcome. Then you must Identify one or more solutions that will lead to a safe landing. Frozen by indecision may mean no decision and hence no corrective action. All the above is irrelevant if the pilot doesn’t Do something. Once corrective actions are decided, the pilot has to implement them. Then Evaluate the action to see if it worked. If not, the DECIDE model may have to be run again. Have a look at the flowchart, integrating PAVE, 3Ps, DECIDE, CARE, TEAM tools in the link!

See more

Decision Making Framework in Healthcare

Click to open

The College of Occupational Therapists of Ontario developed a five-step process for making decisions by occupational therapists. These specialists face all kinds of problems that may require simple or complex decisions. This decision-making framework offers key recommendations about each step of the process.

Step 1. Describe the Situation

The therapists are advised to consider several questions that will help them to understand the situation: What are the key elements of the situation? What are the potential risks associated with the situation? What is the decision to be made? Are there personal assumptions, biases, or cultural differences that could impact decision making?

Step 2. Use the Fundamental Checklist

Six contributing factors that influence the decision-making processes are presented in this step: 1) Client and Family; 2) Organization and Practice Setting; 3) Theories and Evidence; 4) Professional Regulations; 5) Healthcare Team; 6) Law.

Step 3. Consult Others

This step brings forward the importance of different viewpoints and expertise. Some of the parties that may be involved in the decision process are colleagues, supervisors, lawyers or legal professionals, ethicists or an ethics board, regulatory bodies, other clinical or non-clinical professionals or subject matter experts.

Step 4. Identify Options and Choose the Best Action

The main points in this stage are: What makes this the best approach? Does the rationale sound reasonable when you say it aloud? What is your professional instinct telling you? How to recognize and address consequences and document the decision process?

Step 5. Evaluate the Decision

In this phase, the therapist must identify the lessons learned.

See more

TEST

10 QUESTIONS

Click to open

Keywords:

Judgement, biases, types of decisions, decision-making process, tools for decision making

Learning outcomes:

After completing the module “Judgement and Decision Making”, students will gain an understanding of:

- the link between perception and judgment.

- prejudices and biases that might cloud judgement.

- various types of decisions.

- the different steps in the process of decision making.

- some factors influencing the process of decision making.

- individual and group decision making.

Students will develop practical skills in applying:

- a range of decision-making tools.

- various methods to stimulate creativity in decision making.

Bibliography:

- Armstrong, L. (2021). Decision tree diagrams: what they are and how to use them | MindManager Blog. Retrieved 14 November 2021, from https://blog.mindmanager.com/blog/2021/05/11/decision-tree-diagrams/

- Carpenter, M., Bauer, T., & Erdogan, B. (2012). Principles of Management. Retrieved 13 November 2021, from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/principlesmanagement/chapter/11-2-understanding-decision-making/

- De Smet, A., Jost, G., & Weiss, L. (2019). Three keys to faster, better decisions. Retrieved 14 November 2021, from https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/three-keys-to-faster-better-decisions

- Decision Making Techniques. Retrieved 13 November 2021, from https://www.decision-making-solutions.com/decision_making_techniques.html

- Emotional Decision Making. Retrieved 13 November 2021, from https://www.decision-making-solutions.com/emotional_decision_making.html

- Gavin, M. (2020). 5 Key Decision-Making Techniques for Managers | HBS Online. Retrieved 15 November 2021, from https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/decision-making-techniques

- Gibson, J., Ivancevich, J., Donnelly, J., & Konopaske, R. (2012). Organizations: Behavior, Structure, Processes. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Guo, K. (2008). DECIDE. The Health Care Manager, 27(2), 118-127. doi: 10.1097/01.hcm.0000285046.27290.90

- Huang, L. (2019). When It’s OK to Trust Your Gut on a Big Decision. Retrieved 13 November 2021, from https://hbr.org/2019/10/when-its-ok-to-trust-your-gut-on-a-big-decision

- Kay, J. (2020). The D.E.C.I.D.E. Model: A Tool For Teaching Students How to Making Healthy Decisions - Project School Wellness. Retrieved 12 November 2021, from https://www.projectschoolwellness.com/the-d-e-c-i-d-e-model-a-tool-for-teaching-students-how-to-making-healthy-decisions/

- Likierman, A. (2020). The Elements of Good Judgment. Retrieved 9 November 2021, from https://hbr.org/2020/01/the-elements-of-good-judgment

- McBurney, P. What makes some decisions complex?. Retrieved 14 November 2021, from https://www.gdrc.org/decision/complex-decisions.html

- McShane, S. and Von Glinow, M. (2010). Organizational behaviour. Boston: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

- Melendez, C. (2020). Council Post: Lead With Your Gut And Follow The Data: A Decision-Maker's Guide To Success. Retrieved 13 November 2021, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2020/04/17/lead-with-your-gut-and-follow-the-data-a-decision-makers-guide-to-success/?sh=79887abd79cb

- Saylor Academy. (2012). Principles of Management. Retrieved 14 November 2021, from https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_principles-of-management-v1.1/s15-02-understanding-decision-making.html

- Schermerhorn, J., Osborn, R., & Hunt, J. (2002). Organizational behavior. New York: Wiley.

- Serafimova, D. (2015). Teoria na upravlenieto [Management theory]. Varna: Univ. izd. Nauka i ikonomika.

- Simonds, F. (2016). Good Pilot Decision Making - IFR Magazine. Retrieved 14 November 2021, from https://www.ifr-magazine.com/training-sims/good-pilot-decision-making/

- Soosalu, G., Henwood, S., & Deo, A. (2019). Head, Heart, and Gut in Decision Making: Development of a Multiple Brain Preference Questionnaire. SAGE Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019837439

- Stoll, J. (2019). ‘Feel the Force’: Gut Instinct, Not Data, Is the Thing. Retrieved 13 November 2021, from https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-secret-behind-starbucks-amazon-and-the-patriots-gut-instinct-11571417153?mod=djemCIO

- Tichy, N., & Bennis, W. (2008). Judgment: How Winning Leaders Make Great Calls. [Concordville, PA]: Soundview Executive Book Summaries.

Reference link:

- https://www.atlassian.com/work-management/strategic-planning/decision-making/models

- https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/career-development/decision-maker-model

- https://hr.mit.edu/learning-topics/teams/articles/models

- https://careers.gazprom-mt.com/blog/the-different-decision-making-models-you-need-to-know-and-their-pros-and-cons/

- https://www.sinnaps.com/en/project-management-blog/decision-making-model

- https://www.mtdtraining.com/blog/decision-making-models.htm

- https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/the-benefits-and-limits-of-decision-models

- https://www.gold.ac.uk/short-courses/psychology-decision-making/

- https://memory.ai/timely-blog/8-types-of-bias-in-decision-making

- https://neuroleadership.com/your-brain-at-work/seeds-model-biases-affect-decision-making/

- https://www.masterclass.com/articles/how-to-identify-cognitive-bias#12-examples-of-cognitive-bias.

- https://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/personality-quiz/

- https://www.16personalities.com/personality-types

- https://www.economist.com/johnson/2011/05/27/this-may-interest-you

- https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/chart-shows-what-british-people-say-what-they-really-mean-and-what-others-understand-a6730046.html

- https://www.mindtools.com/media/Images/Infographics/The_Vroom_Yetton_Decision_Model_final.pdf

Video:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wXnBvcuzAOE

- Videos from Dubicka, I., Rosenberg, M., Dignen, B., Hogan, M., Wright, L. „Business Partner’, B2+, Coursebook with Digital Resources, Pearson, 2019

- https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/video/2017/jan/22/kellyanne-conway-trump-press-secretary-alternative-facts-video

- https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=10155079740661800

Play Audio

Play Audio